Sitting quietly before evening Mass in Dublin’s Pro-Cathedral yesterday evening my thoughts went towards the Feast we celebrate today, the Feast of All Saints. I reflected much on the inspirational lives of deceased members of my own family, some who had experienced World War I and had lived through the hardships of modern Ireland’s early years. All of those who came to mind during those moments were people I had known as devout prayerful Catholics living modest lives and caring for others, especially the poor in their respective parishes. There was no ‘social protection’ in those days. So much depended on the now much derided ‘Catholic charity’. All of them are, in my view truly saints.

The priest, the Canon of the Pro-Cathedral, gave an excellent, well-prepared homily in which he touched on similar points, evoking his own twin-sister, happily still alive and giving selflessly to the care of a daughter who lives with severe disability. As Canon O’Reilly pointed out to us, sanctity is about doing the ordinary things of life extraordinarily well. An old phrase but one that still rings with the truth it expresses.

In front of me in the pew there was a young Italian family who seemed either to have just arrived or were set to depart as they had their suitcases with them. I wondered about what drew them to the church, its proximity to O’Connell Street and the airport bus stop perhaps, or was it because of the church’s reputation for good music. I also wondered about their lives and what sanctity would mean for them. To attend Church today in modern Ireland is an act of cultural rebellion, a considered option that suggests awareness and conviction as well as deep faith.

And, it is, somewhere there that I discern the ‘holy’ dimension of what being a saint means. My own family experience, which I am certain is shared by many, suggests that being, or becoming, a ‘saint’ is about a commitment to living out our humanity fully in all its dimensions. Many people today opt to live humanly in a few dimensions: socially and culturally, but not spiritually, and certainly not religiously.

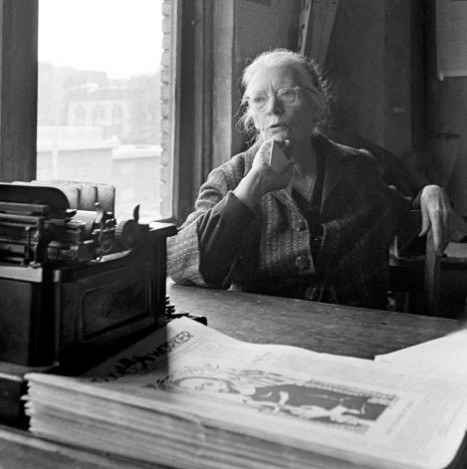

Somewhere in the back of my mind there was an echo of modern people in times past who had expressed the desire to be a saint. Saint Thérèse of Lisieux comes to mind, but also people like Etty Hillesum, Simone Weil and Dorothy Day. Thomas Merton, too, as I recall in his Seeds of Contemplation. I am sure they did not have in mind canonised sainthood, but the ordinary sainthood of living out our humanity fully in all its dimensions in imitation of Jesus of Nazareth. They also had in view the example of the lives of canonised saints whose stories once inspired us. Less so. now, for all the obvious reasons.

Robert Ellsberg has a wonderful article in America magazine where he explores this way of seeing what it is to be a saint. He takes as his focus the current campaign to have Dorothy Day declared a canonised saint. He takes on the criticism that Dorothy Day was not conventionally pious; she certainly was not so. But she witnessed to the kind of stout-hearted rough-hewn Catholicism that I admired in my own family. Peter Maurin, her mentor, often shared with Dorothy just such a notion of what it is to be saint. He put before her a model of heroism and selflessness that she certainly lived out in her work with the poor and the homeless.

See this article here