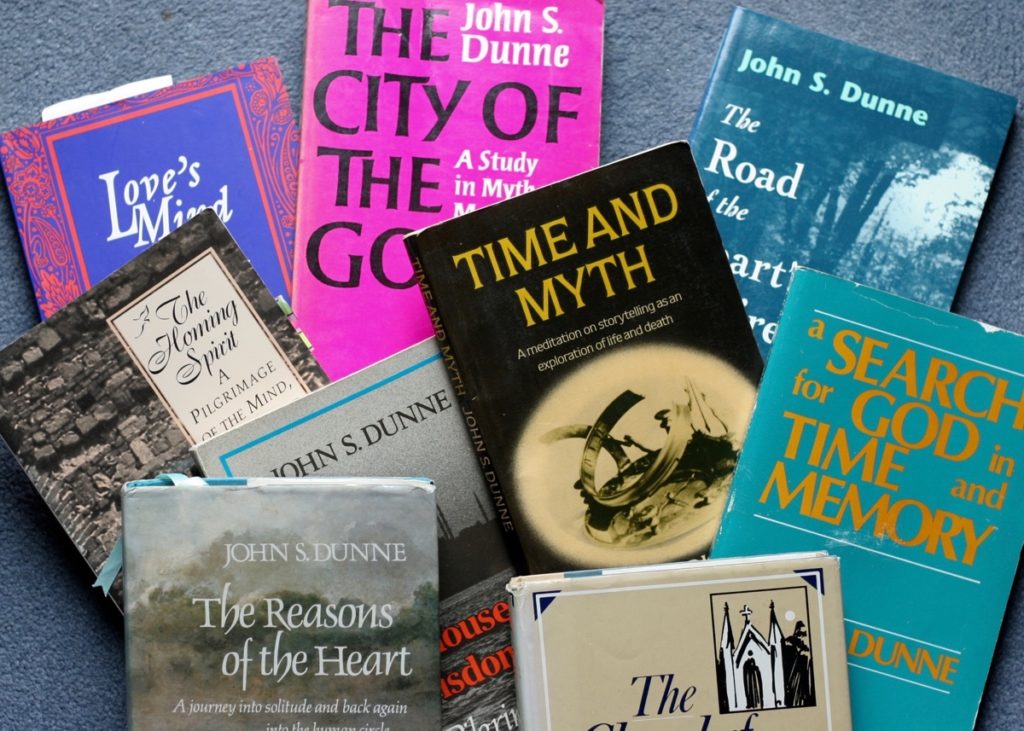

Tidying my shelves the other day I came across a set of books carefully lined up. All were books by the University of Notre Dame scholar, priest and spiritual guide, Father John S. Dunne csc. He died some years ago in 2013. What John S. Dunne explored was a process that is key to the discernment of vocation. He explored in his writings what it means to be fully human. However, he was not writing about psychology although he was more than familiar with its perspective. Instead, he undertook the most arduous journey of all, an investigation of his own inner thoughts, feelings and moods in the context of his relationships. For anyone who is seriously engaged with the call to religious life, an openness to undertaking this journey is essential.

Becoming a religious is not like sending in a job application. It is a journey that one undertakes. Sometimes, in fact most often, it begins simply with the willingness to undertake spiritual practices like prayer, whether it by the Rosary, Mass, spiritual reading, participating in a youth group, or keeping a journal. All such experience open up a path for us. John S. Dunne and Thomas Merton are two people for whom this journey was central to their lives, both at the point where they began thinking about religious life and throughout their lives. We can learn a lot from them.

This past while I have also been immersed in a biography of Thomas Merton by Monica Furlong simply entitled Merton, A Biography, first published in the UK in 1980. Reading this book, and especially the biographer’s recounting of Merton’s later years, I was struck by so many parallels with John S. Dunne.

Both were American priests with a strong rootedness in American life. Merton was already dead when Dunne began writing. There were, however, literary and artistic relationships that wove them both into the same story: Flannery O’Connor, Dorothy Day, T. S, Eliot, and so many writers and thinkers from the vast panorama of Western culture and philosophy. Both became fascinated early on by the contact with Eastern philosophy and mysticism. And both had been drawn into the late 20th century struggle for justice in Latin America. It was left to Dunne, however, to make the journey to Latin America that Merton never did.

Some books by John S. Dunne cfc

An Awakened Spirit

What ultimately links both writers is their commitment to the inner life and their fascination with the journey of the self. This journey was a particularly modern one, albeit with roots in Augustine. Early in his writing John S. Dunne picks up this thread from Kierkegaard, Hegel and the poetry of Rilke. For Merton, the quest for authentic living was hard won in the teeth of opposition from religious authorities and the accepted limitations of his enclosed life as a Trappist monk. Dunne described the quest as shaped by the desire to become, as he said, ‘heart-free’.

Although Merton spoke much about solitude, he comes later to the insight that his ultimate quest is the ‘search for God. Oddly enough, this was the title of one of Dunne’s first books, A Search for God in Time and Memory (1977). Much of Dunne’s writing over the years was devoted to the nature of the spiritual quest. Had Merton been reading Dunne he would have been struck by the number of times that Dunne describes his work in terms of insight and discovery. Life is a process of making discoveries. Not too hard to discern the influence of Lonergan somewhere in the background here.

Becoming Heart Free

As a graduate student at the Institut Catholique in Paris, I undertook an analysis of Dunne’s corpus as it was at that time in the early 1980s. It took the form of a thesis, directed by the late Père Kowalski, and it took for its title, Becoming Heart-Free. I later fetched up at Notre Dame where I met John S. Dunne and many of his colleagues. He was a revered figure on campus, much sought after by young college students. His influence on their lives was obvious to all. He was a charismatic figure in the fullest sense. His place of ministry was the college lecture hall. But many flocked to see him for spiritual direction and advice. Like Merton, he spent much of time writing writing, thinking, contemplating. In a move similar to that of Merton’s, John sought to live closer to people by moving off campus to a simple house on the corner of a South Bend street.

Both men were seriously aroused in their spiritual core by aesthetic experience. Artists such as Klee, Rouault , Rothko, and Kandinsky resonated deeply with their spiritual imagination. Something in the artistic theme of the outsider, of the pilgrim, of the loner found in these works touched their psyches. Rilke, too, was an important poet who spoke to the experience of loneliness (or ‘aloneness’ as Dunne would say) that sharpened their spiritual sensibilities and eventually opened up for them the wider world of relationship. For men with a clear contemplative orientation this a path of discovery and insight that they both shared.

There is a Way

Each in his own way undertook an inner journey that called each away from the narrow conventions of 1950s America towards the wider horizons of a suffering world. In their respective journeys their dialogue partners were artists, poets, writers and contemplatives from many spiritual traditions. While, in a sense, Father Dunne travelled the world in imaginative ‘thought experiments’ without ever leaving Notre Dame, Merton did the same without leaving his monastic enclosure.

Everywhere John S. Dunne perceived the unity of the spiritual quest across time, across cultures and across the varieties of religious experience. In what is for me a favourite expression of his, he articulated this unity and universal dimension of experience when he repeated, as he did throughout his writing:

Things are meant. There are signs. There is a way.

Like Merton, Dunne’s search throughout his life was for the authentic path, the way of truth, that would lead him to an iner harmony of life, the world and the spirit. Merton perceived a similar resolution of his own spiritual quest when he said:

Coming to the monastery has been for me exactly the right kind of withdrawal. It has given me perspective. It has taught me how to live. And now I owe everyone else in the world a share of that life. My first duty is to start, for the first time, to live as a member of the human race which is no more (and no less) ridiculous than I am myself. From the The Sign of Jonas, 1953.

Leave a Comment