This afternoon, sitting in the Avalon backpacker’s café I pondered Ash Wednesday and what it might mean. For many today it is a ritual devoid of relevance for life or faith. An RTE radio presenter said this morning, “I have no idea what it’s all about.” Time was when on this day the foreheads of passers by on the street splotched with the ritual ashes were a commonplace. Not so today.

I finished my coffee and headed into the nearby Carmelite church where I knew there was a priest on duty. The church was warm, welcoming and an oasis of quiet in the city. A priest, brown habited and clearly a man of many years, stood near the first pews. A sporadic trickle of people went up to him, crossed themselves, and received the ashes on the forehead. It was an ancient ritual, marked by the apparent casualness of habit but still retaining some connection to the faded beliefs of the past.

As I, too, crossed myself, I heard the priest say the words, “Remember that Thou art dust and unto dust you shall return,” as he signed the ashes on my forehead, I felt myself entering for a brief moment some coincidence of my past, my present and my future life beyond death. The priest said, “Thank you for coming” and prepared himself to welcome the next seeker of cleansing and consolation.

I was reminded of T. S. Eliot making his wartime visit to the village of East Coker in Somerset. A person of strong religious faith that found expression in his poetry, Eliot revealed in The Four Quartets, an acute sense of time, time present and time future, condensed into the discrete moments of transcendence. It was for him a kind of reaching out for the eternal, for cosmic wholeness, in today’s language. The famous often quoted words, “In my beginning is my end … “, echo the words of the Ash Wednesday ritual Are we secularised people still open to this fusion of time and eternity? Eliot thought so. Otherwise, to use his words, we would ‘miss the meaning’.

Ritual, at its best, opens up for us in the casual simplicity of a gesture an intimation of the cosmic eternal moment which alone makes the discrete discordances of our lived experience ultimately meaningful. It bestows a kind of redemption. Eliot sought redemption in language but his poetry often contains echoes religious ritual. He could discern the mystery of things in nature, in gesture, in the pain of life, with which he himself was personally familiar. A light shines in the darkness.

“Be still and let the darkness come upon you, which is the darkness of God” (T. S. Eliot, The Four Quartets)

Something to Do

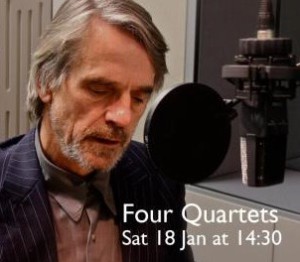

Listen to Jeremy Irons read the Four Quartets here. It might help to ritualise this beginning of Lent in a quiet hour.

Thanks for the above Donal, good soul food in a spiritual wasteland. On Ash Wednesday I explained to the lady that it did’nt really make a lot of sense to put the ash on the little baby’s head. This beautiful child was no sinner, nor could he repent. Nor did he need a reminder that he would return to God. ‘Ah Father, sure it’ll do him no harm, it’ll protect him and give him healing’. I did not believe that, but she clearly did. Superstition? Blind faith? What remains?

Joe, thank you for your thoughtful comment and I agree entirely with it. It is one of the interesting things about the ashes ritual that it seems touch people who otherwise do not engage with church. I saw somewhere this week a reference to someone who never goes to church, not even for christmas, but will still show up for the ashes. Superstition? Maybe. I’m inclined to think that it suggests soul-speak for connection.

Thank you Donal for your reflection on Ash Wednesday. Interesting that you chose the backpackers café as the locus to begin your reflection on this “Spring time” for Christians. I had ashes on my forehead from early that morning and as I waited for the bus was conscious of who else might. I observed a certain relief that my head covering had muted the mark somewhat yet not totally. So I too am subtly conditioned by the current thinking represented by the comment of your friend on RTE.

Thanks for that reflection Donal and I appreciate Joe and Martin’s comments too. What occurs to me is I used to react against the “Dust thou art ….” blessing and even discouraged it in rituals we had when I was in Zimbabwe. Now, however, in the light of the Cosmic story, it has more meaning. As does the call to repentance, of course. When I was passing through Tralee on Wednesday, I noticed a significant number of people with ashes on their foreheads.

I agree that giving and receiving ashes is a beautiful and meaningful ritual. My false ego needs to be reminded of my creaturehood. Isn’t it strange that on the two days that are not “days of obligation” – Ash Wednesday and Good Friday – churches are often full. These rituals strike a deep core within many people.