In the Third Week of Advent, in Luke 3:7–18, we are with John the Baptist in the wilderness of Judaea. He is preaching to the people. The people are flocking to him from all walks of life: fishermen from Lake Galilee, Roman soldiers, local farmers, seekers of wisdom, the curious.

Why do they come to him? Because, somehow, they have a sense that here is someone who tells it like it is. In that regard he’s not unlike our current Pope, Pope Francis. He is someone who speaks to people in everyday language and can illustrate a point with a memorable metaphor. Remember Pope Francis telling priests that they should have ‘the smell of the sheep’ on them. Be among the people.

Why waste your one precious life?

John the Baptist whom we hear this week in the Sunday reading for the Third Sunday of Advent is a plain speaker. Just imagine if he had had Twitter available to him! He is speaking to us, plainly, bluntly, with a slightly caustic turn of phrase. That’s time spent in the wilderness of Judaea would do to you. You would shed a great deal of deference and see things with razor-sharp clarity.

For example, in Luke 3:8–9 he calls the people “a brood of vipers”. That would be like referring to one’s listeners, in contemporary language, as a ‘crowd of wasters’! It would get people’s attention straight away, but not in a manner that would make too many friends. But that’s John the Baptist for you. He then goes on to say that trees that are a ‘waste of space’ should be cut down, or words to that effect. He uses the image of a useless tree about to be burned as firewood.

What is a life worth living?

There is a message here for us as we reflect on the direction of our lives. It’s about how to live a good life, a fulfilled life.

David Cameron spoke about this in societal terms in 2006 when he reflected on the kind of pre-financial-crash society we had back then. We remember it as a time when people were chasing easy money and the next lucrative property deal. It was a crass form of capitalism. Here’s what he said:

It’s time we admitted that there’s more to life than money, and it’s time we focused not just on GDP, but on GWB – general well-being. Well-being can’t be measured by money or traded in markets. It can’t be required by law or delivered by government. It’s about the beauty of our surroundings, the quality of our culture, and above all the strength of our relationships. Improving our society’s sense of well-being is, I believe, the central political challenge of our time.

One of my favourite contemporary writers at the moment is Roger Scruton, an English philosopher who also writes along these lines. He reminds us of the ways in which we ‘waste’ our lives by becoming hooked on the celebrity media culture. What we are missing is the beauty of the natural world and the joy of being with others in conversation.

What is the Good Life?

Cameron spoke about ‘well-being’. Irish schools are about to introduce a course on well-being as a secular substitute for lessons on morality. As it happens this is the new contemporary way of speaking about what in former times we called ‘the good life’, ‘a happy life, or ‘a fulfilled life’.

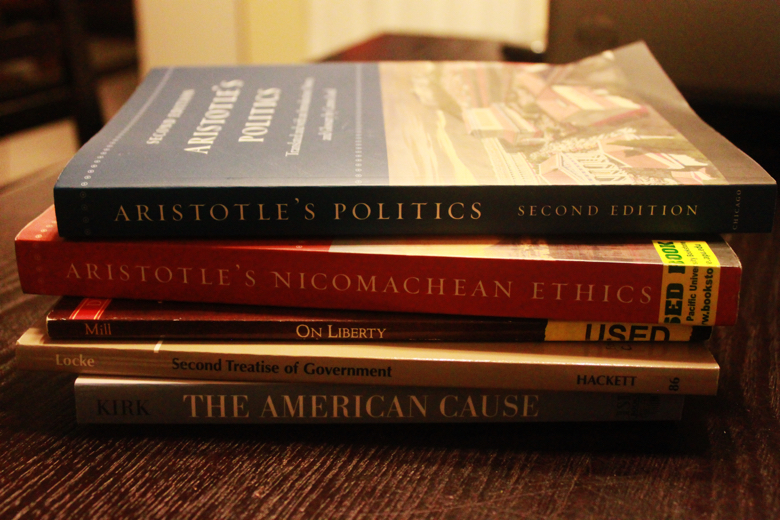

Back in the day, very far back, the Greeks reflected much on this topic. Aristotle devoted a whole book to the topic; it was called the The Nicomachean Ethics<. He. too, like Jesus of Nazareth, and, indeed, David Cameron, said that there is a lot more to life than our popular notion of what counts as ‘success’ or, feeling good about yourself, for that matter.

There is nothing more tragic than a life wasted or oriented in the wrong direction. I recall someone saying once that there is nothing worse than to find out, in the striking metaphor of Joseph Campbell in his book, The Power of Myth, that your “ladder has been up against the wrong wall”. Nothing worse than making bad choices. The popular newspapers and media are replete with examples of people who made bad choices leading sometimes to self=destructive outcomes.

What am I to do?

The important thing is to be attentive to the questions that arise for us. Feelings of unease about where we are, a certain ‘stuckness’ may be the prompt that we need to stand back a little and assess our direction in life.

This is fertile ground for the still small voice that is God’s word to us. The answer to the question, what am I to do, slowly emerges. It is more like a process than a fully disclosed answer.

“What am I to do?” is a question that, thankfully, remains with us for life. The challenge is to stay with the question.

Leave a Comment